By Harshit

NEW DELHI, DECEMBER 16, 2025

From the warmth of sunlight on skin to the sharp jolt of pain after an injury, conscious experience shapes every moment of daily life. Pleasure, discomfort, fear, and even prolonged suffering are not accidental byproducts of biology—they are deeply embedded features of how living beings interact with the world. A central scientific question has long persisted: why did evolution produce minds capable of such rich, and sometimes distressing, experiences?

Recent work by philosophers and neuroscientists suggests that consciousness evolved not as a single trait, but as a layered system serving survival, learning, and social coordination. Research spanning humans, mammals, and birds now points to consciousness as an ancient biological strategy rather than a uniquely human phenomenon.

Three Forms of Consciousness

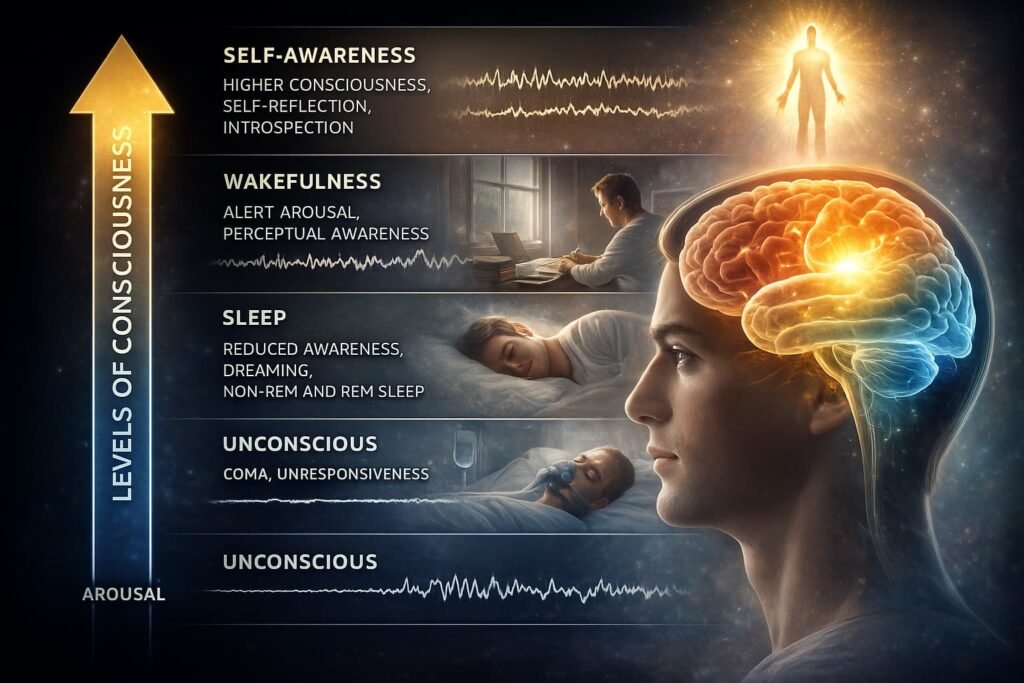

Philosophers Albert Newen and Carlos Montemayor describe consciousness as emerging in three major forms, each associated with a different evolutionary function.

The most basic form is arousal, a primitive state that places the body on high alert during danger. According to Newen, this was likely the earliest form of consciousness to evolve. Its primary function is survival. Pain plays a central role here by signaling bodily damage and triggering immediate responses such as fleeing, freezing, or withdrawal. In evolutionary terms, pain is an efficient alarm system—costly in experience, but vital for staying alive.

Attention as an Evolutionary Upgrade

A later evolutionary development is general alertness, which allows organisms to selectively focus on important signals while ignoring background noise. This form of consciousness supports learning and decision-making.

For example, noticing smoke while talking to someone instantly redirects attention toward a potential fire. Montemayor explains that this selective focus enables organisms to learn causal relationships—first simple ones, like smoke indicating fire, and later more complex patterns that underpin scientific reasoning and abstract thought.

This capacity for attention filtering represents a critical step beyond reflexive responses. It allows experience to be shaped by relevance rather than immediacy.

Self-Consciousness and Social Life

The most advanced form of consciousness is reflexive, or self-consciousness. This ability enables individuals to reflect on themselves, recall past experiences, anticipate future outcomes, and form a mental self-model.

Newen notes that this form of consciousness developed alongside the more basic types rather than replacing them. Reflexive consciousness shifts awareness inward, toward bodily states, thoughts, emotions, and actions. In humans, this capacity typically becomes visible around 18 months of age, when children recognize themselves in mirrors.

Self-consciousness plays a crucial role in social life. It supports coordination, cooperation, and the ability to understand oneself as part of a group. Certain non-human animals—including chimpanzees, dolphins, and magpies—have also demonstrated elements of this ability, suggesting it evolved independently across species.

Consciousness Beyond Mammals

Growing evidence indicates that consciousness is not limited to mammals. Research by neuroscientists Gianmarco Maldarelli and Onur Güntürkün suggests that birds exhibit several key features associated with conscious experience.

Studies of sensory perception show that birds do more than react automatically to stimuli. When pigeons are shown ambiguous images, they alternate between different interpretations, mirroring human perceptual experience. In crows, specific neural signals correspond to what the animal perceives rather than the physical stimulus itself. When a stimulus is sometimes detected and sometimes missed, neuronal activity reflects that internal experience.

Bird Brains and Conscious Processing

Bird brains differ anatomically from mammalian brains, lacking a layered cerebral cortex. Yet they contain functionally comparable structures. Güntürkün points to the nidopallium caudolaterale (NCL), often described as the avian equivalent of the prefrontal cortex.

The NCL is highly interconnected and supports flexible information integration. Mapping of avian brain connectivity shows strong parallels with mammalian neural networks. According to Güntürkün, these similarities align birds with established theories of consciousness, including the Global Neuronal Workspace theory, which emphasizes widespread information sharing across the brain.

Signs of Self-Perception in Birds

Evidence also suggests that some birds possess basic forms of self-perception. While certain corvids pass the traditional mirror test, other species show context-sensitive responses that indicate situational self-awareness.

Experiments reveal that pigeons and chickens can distinguish between their reflection and another bird and respond appropriately depending on the situation. This ability suggests a rudimentary form of self-consciousness, one adapted to ecological and social needs rather than human-style introspection.

An Ancient and Widespread Trait

Taken together, these findings challenge the idea that consciousness emerged late or exclusively in humans. Instead, consciousness appears to be an ancient evolutionary solution—one that arose multiple times in different biological forms to support survival, learning, and social interaction.

Birds demonstrate that conscious processing does not require a cerebral cortex and that very different brain architectures can produce similar functional outcomes. Consciousness, in this view, is not a luxury of intelligence but a deeply rooted biological tool shaped by natural selection.