By Harshit

PACIFIC OCEAN, jan 6 —

A chance satellite observation has given scientists their clearest view yet of how massive tsunamis actually behave as they race across the open ocean—and the picture is far more complicated than decades of theory suggested.

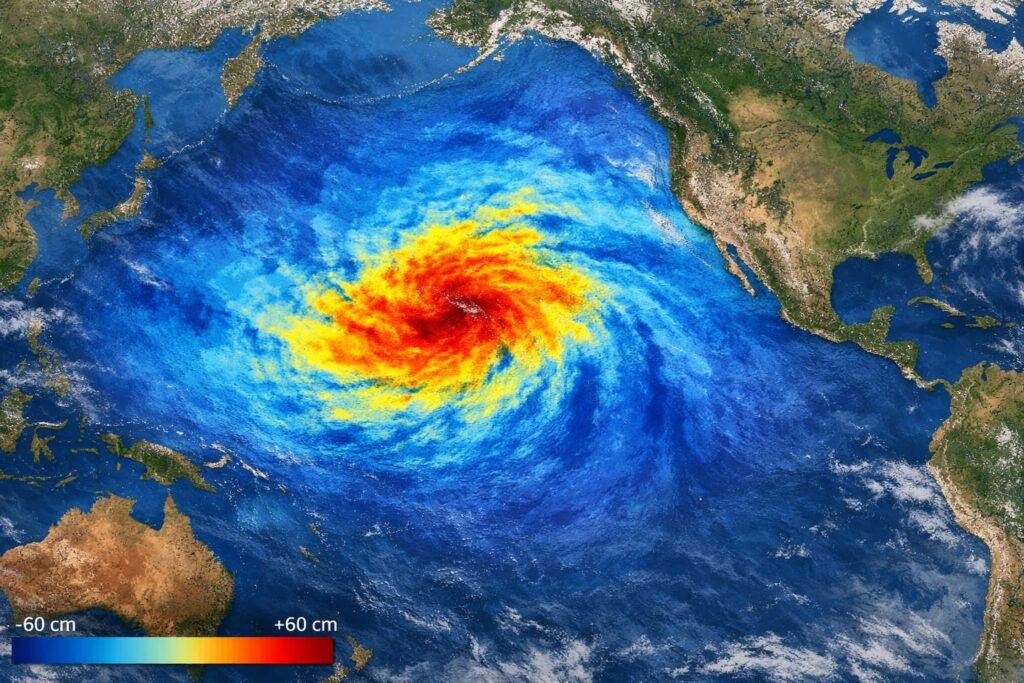

In late July, a powerful earthquake off Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula generated a tsunami that rippled across the Pacific. At that exact moment, a satellite built to measure subtle changes in sea surface height passed directly over the wave. The result was the first high-resolution, space-based track of a major subduction-zone tsunami, captured almost accidentally.

The data, reported in The Seismic Record, shows that large tsunamis do not move as single, clean waves. Instead, they fracture into complex patterns of interacting wave fronts that scatter energy across the ocean basin—behavior that could affect how these waves intensify near coastlines.

A Rare Satellite Alignment

The spacecraft responsible for the observation is the Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) satellite, launched in December 2022 to study Earth’s surface water. Its primary mission is to map oceans, rivers, and lakes with unprecedented precision—not to monitor natural disasters.

Yet on July 29, as a magnitude 8.8 earthquake ruptured the Kuril-Kamchatka subduction zone, SWOT happened to cross the tsunami’s path. The quake ranks as the sixth-largest earthquake recorded globally since 1900.

Instead of detecting a smooth, uniform wave, the satellite recorded a wide swath—nearly 120 kilometers across—revealing multiple wave crests spreading, bending, and interfering with one another as they traveled.

Researchers say no previous satellite system has captured this level of spatial detail for a tsunami in the open ocean.

Why Tsunamis Were Thought to Be Simple

For decades, scientists have treated large tsunamis as “non-dispersive” waves. Because their wavelengths are extremely long compared with ocean depth, standard theory suggests they should travel without breaking apart or spreading energy into smaller waves.

The new satellite data challenges that assumption.

“When we compared the observations with numerical simulations, the models that allowed for wave dispersion matched the real tsunami much better,” said lead author Angel Ruiz-Angulo of the University of Iceland. “This tells us we’re missing important physics in the models we’ve relied on for years.”

Dispersion means that different parts of the wave travel at slightly different speeds, causing the tsunami to stretch and develop trailing wave trains—features that were previously difficult to observe across the vast open ocean.

Combining Space and Sea Sensors

To validate the satellite findings, the research team combined SWOT measurements with data from DART (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis) buoys positioned across the Pacific. These seabed-anchored sensors detect minute pressure changes caused by passing tsunamis.

By merging the two data sources, scientists refined their understanding of the earthquake itself. The analysis showed that the rupture likely extended roughly 400 kilometers along the fault—about 100 kilometers longer than earlier estimates.

This revised rupture length helps explain discrepancies in tsunami arrival times recorded by different buoys, where some detected the wave earlier and others later than predicted.

“Ever since the 2011 Japan tsunami, we’ve known tsunami data holds critical information about shallow fault slip,” said co-author Diego Melgar. “This event reinforces how valuable it is to combine ocean and seismic observations.”

Why Complexity Matters for Coastal Risk

The newly observed wave interactions may have real-world consequences. As complex wave trains approach shorelines, trailing waves could amplify or reshape the main surge, potentially altering flooding patterns in ways not fully captured by existing warning models.

Researchers caution that more events must be analyzed before changing forecasting systems, but the findings suggest that tsunami hazards may be more variable—and in some cases more dangerous—than previously assumed.

“This extra energy and variability could matter when the wave reaches land,” Ruiz-Angulo said. “It’s something we need to quantify carefully.”

A Future Role in Tsunami Warnings

The Kamchatka region has produced some of the most destructive tsunamis in recorded history, including a 1952 event that devastated coastal communities and helped spur the creation of the modern Pacific tsunami warning system.

While SWOT was never designed for disaster response, scientists believe similar satellite observations could eventually complement buoy networks and seismic data in near-real-time forecasting.

“With enough coverage and fast processing, satellite altimetry could become another critical layer in tsunami monitoring,” Ruiz-Angulo said.

For now, the unexpected capture stands as a reminder that even well-studied natural hazards can still surprise—and that seeing the ocean from space may change how scientists understand the planet’s most powerful waves.