By Harshit | Cambridge, Massachusetts | October 27, 2025 | 1:00 AM

A Molecular Breakthrough in Atomic Physics

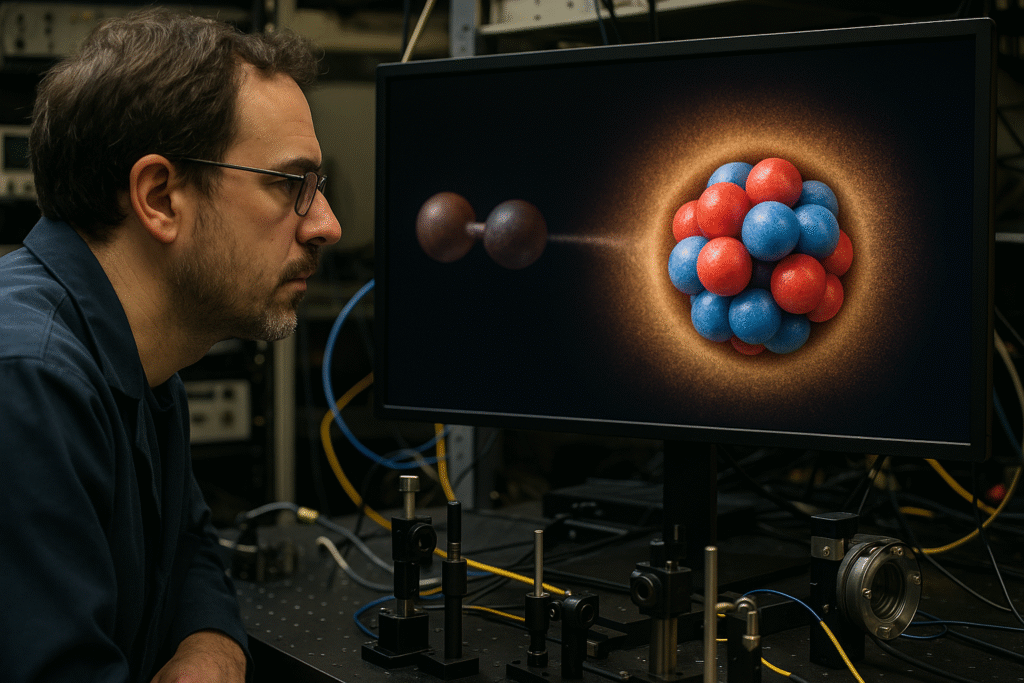

In a major advance for nuclear physics, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed a technique that allows them to peer inside an atom’s nucleus—without the need for massive particle colliders.

The method, published on October 23 in Science, uses the atom’s own electrons as “messengers” to probe the inner structure of the nucleus. By chemically binding a radium atom to a fluoride atom—forming a molecule called radium monofluoride—the researchers created a unique molecular environment that forces electrons to move closer to the nucleus.

As the electrons occasionally penetrate the nucleus and emerge again, they carry with them subtle energy shifts that encode information about the nuclear interior.

Turning Molecules Into Mini Particle Colliders

Traditional nuclear experiments depend on kilometer-scale accelerators, such as those at CERN, to smash high-energy particles into atomic nuclei. The MIT team’s approach achieves something similar—on a tabletop.

“When you embed a radioactive atom like radium in a molecule, the internal electric field experienced by its electrons is vastly stronger than anything we can produce in a lab,” explains Silviu-Marian Udrescu, a study co-author and recent MIT PhD graduate. “It’s as if the molecule becomes a tiny particle collider.”

The research was led by Professor Rogério de Castilho, a nuclear physicist at MIT’s Araçatuba School of Dentistry at São Paulo State University (FOA-UNESP) in Brazil, with contributions from MIT researchers Shane Wilkins, Udrescu, and Alex Brinson, in collaboration with CERN’s Collinear Resonance Ionization Spectroscopy Experiment (CRIS) in Switzerland.

Measuring Electron “Messages” From the Nucleus

Working with small quantities of radium monofluoride—since radium is radioactive and scarce—the scientists cooled and trapped the molecules, then illuminated them with finely tuned laser light to measure electron energies.

They discovered a minute but measurable energy shift that could only be explained if some electrons had entered the nucleus and interacted with its internal protons and neutrons.

“There are many experiments that study how electrons interact with the nucleus from the outside,” says Wilkins, the study’s lead author. “But when we compared our precise measurements with theoretical predictions, the numbers didn’t add up—unless we considered that some electrons were actually going inside the nucleus.”

The effect was tiny—just one-millionth of the energy of the laser photon used in the experiment—but it provided clear evidence that electrons were directly probing nuclear matter.

Why Radium Matters: The Pear-Shaped Nucleus

Most atomic nuclei are roughly spherical, but radium’s nucleus is distinctly pear-shaped, with an uneven distribution of mass and charge. This asymmetry makes radium uniquely suited for experiments seeking to detect violations of fundamental symmetries, such as those that may explain why the universe contains more matter than antimatter.

“The radium nucleus acts as an amplifier of symmetry breaking,” says Garcia Ruiz. “Because of its unusual shape, even tiny asymmetries in the laws of physics could become detectable.”

Understanding these effects could help answer one of cosmology’s deepest mysteries—why the Big Bang produced a universe dominated by matter, when theory predicts equal parts of matter and antimatter.

From Tabletop Physics to Cosmic Questions

The researchers believe their new molecular approach can reveal the nuclear magnetic distribution—the pattern of tiny magnetic fields generated by protons and neutrons within the nucleus. Mapping this feature could provide clues to the internal arrangement of nuclear matter and potential sources of symmetry violation.

“Now that we’ve proven we can detect interactions inside the nucleus,” says Garcia Ruiz, “the next step is to map the internal structure of radium nuclei and search for signals that might point to new physics.”

Future experiments aim to cool the radium monofluoride molecules even further and align their pear-shaped nuclei to enhance measurement precision.

A Compact Window Into the Subatomic World

This breakthrough marks a shift toward more accessible, small-scale nuclear research, enabling physicists to explore phenomena once reserved for giant accelerators.

“Think of it like measuring a battery’s electric field,” Garcia Ruiz adds. “We’ve always been able to measure outside the battery. Now, for the first time, we can measure what’s happening inside.”

If the method continues to develop, it could provide unprecedented insights into the forces shaping atomic nuclei, testing the limits of the Standard Model and offering new clues to the origins of matter itself.