By Harshit | October 19, 2025 | Osaka, Japan | 4:30 AM JST

In a quiet lab at Japan’s Kyushu University, developmental biologist Katsuhiko Hayashi is working on something that could transform the future of human reproduction — growing eggs and sperm entirely in the laboratory. His decades-long pursuit is not only a quest to understand how life begins at the cellular level but could also one day rewrite the rules of fertility, parenthood, and even genetics.

The Long Road to Reproductive Innovation

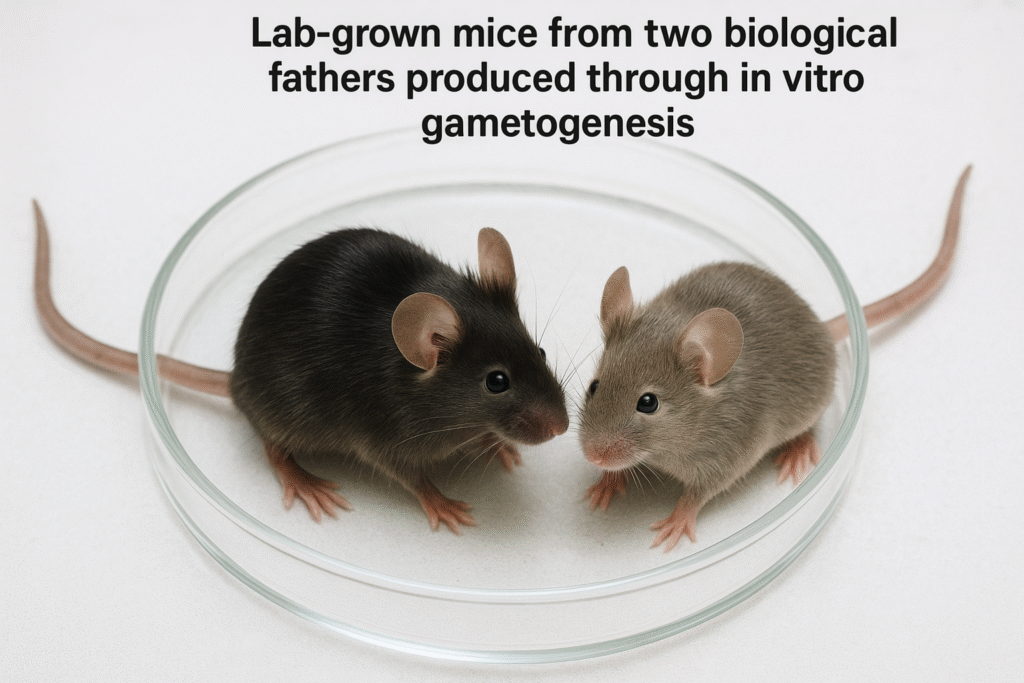

For more than two decades, Hayashi has dedicated himself to studying how stem cells can be coaxed into becoming reproductive cells — a process known as in vitro gametogenesis (IVG). His research group has already achieved milestones once thought impossible, such as producing mice born from two biological fathers and no mother.

“It’s been a torturous but rewarding journey,” Hayashi admits. “Each discovery brings both excitement and new challenges.”

Despite the scientific breakthroughs, Hayashi is constantly flooded with pleas from couples seeking help with infertility. “I tell them this is still experimental,” he says. “We’re not ready for human use yet.”

Promise and Precaution

The implications of Hayashi’s work are immense. IVG could give hope to millions of infertile couples and even make it possible for same-sex partners to have genetically related children. However, experts warn that the road from the lab bench to the clinic remains long and uncertain.

“The technology is fascinating, but it’s nowhere near clinical readiness,” said Christian Kramme, Chief Scientific Officer at the fertility-focused biotech company Gameto. “It may take a decade or more before any safe human application.”

In the meantime, scientists are finding other uses for lab-grown gametes. Pharmaceutical researchers hope that abundant supplies of artificial eggs and sperm could make it easier to test whether new drugs affect fertility or cause heritable genetic damage.

Understanding the Science of Life

Creating eggs and sperm in the lab requires reprogramming normal body cells into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which can transform into nearly any type of tissue. These stem cells are then guided through the complex stages of gametogenesis, the natural process by which the body forms eggs and sperm.

In humans, egg development begins before birth. Immature eggs, called oocytes, lie dormant for years before resuming development at puberty. Sperm cells, by contrast, begin forming during adolescence and are produced continuously throughout adulthood.

Replicating this intricate process in a dish is extraordinarily challenging. “Each stage involves numerous environmental cues — mechanical, hormonal, and molecular,” explains Azim Surani, a developmental biologist at the University of Cambridge. “Even a small deviation can derail development.”

Lab-Built Gonads and 3D Organoids

To mimic natural reproductive environments, Hayashi’s team and others have engineered miniature ovary and testis-like structures. In one experiment, they cultivated fragments of artificial ovaries to nurture developing egg cells. In another, they used 3D-printed testicular tubules made from human cells to simulate sperm production.

At the University of British Columbia, urologist Ryan Flannigan is experimenting with similar 3D structures, while other labs employ microfluidic devices to mimic the natural flow of fluids inside the reproductive organs.

But survival remains a key issue. “Our testicular organoids die before gametes fully mature,” said Ina Dobrinski, a reproductive biologist at the University of Calgary. “In humans, egg and sperm maturation takes months — replicating that in the lab is incredibly hard.”

The Genetic Challenge: Perfecting Meiosis

Perhaps the biggest barrier lies in replicating meiosis — the special cell division that halves the number of chromosomes, ensuring genetic balance in offspring. Faulty meiosis can lead to chromosomal abnormalities and infertility.

Researchers such as Paula Cohen at Cornell University have spent a decade trying to coax immature human gametes to complete normal meiosis in the lab. “So far, it doesn’t work perfectly,” Cohen admits. “Some teams claim success, but we haven’t seen fully authentic meiosis outside the body.”

Recent experiments have shown partial success. In one study, scientists replaced the nucleus of an immature egg with that of a skin cell and triggered a process mimicking meiosis, producing egg-like cells that could be fertilized. Yet most of the resulting embryos had chromosomal errors, underscoring how far the field has to go.

Ethics and Regulation

While many researchers focus on medical benefits, others are concerned about the potential misuse of the technology. If scientists can one day produce vast numbers of artificial gametes, it might enable embryo selection for desirable traits or even genetically modified children.

Governments and bioethics panels are already calling for strict regulations before human IVG becomes possible. “This field has enormous potential — both good and bad,” said Mitinori Saitou of Kyoto University. “We must proceed with scientific responsibility.”

The Future of Fertility

Hayashi believes that the first lab-grown human egg-like cells could appear within two years, but creating fully functional eggs capable of producing healthy embryos will take far longer — perhaps five to ten years.

“It’s not just about creating life in a dish,” he says. “It’s about understanding the essence of life itself.”

For now, his work remains a mix of scientific wonder and ethical complexity — a reminder that the line between what we can do and what we should do is growing ever thinner.