By Harshit

IRVINE, CALIFORNIA | November 23, 2025 | 01:40 AM PST

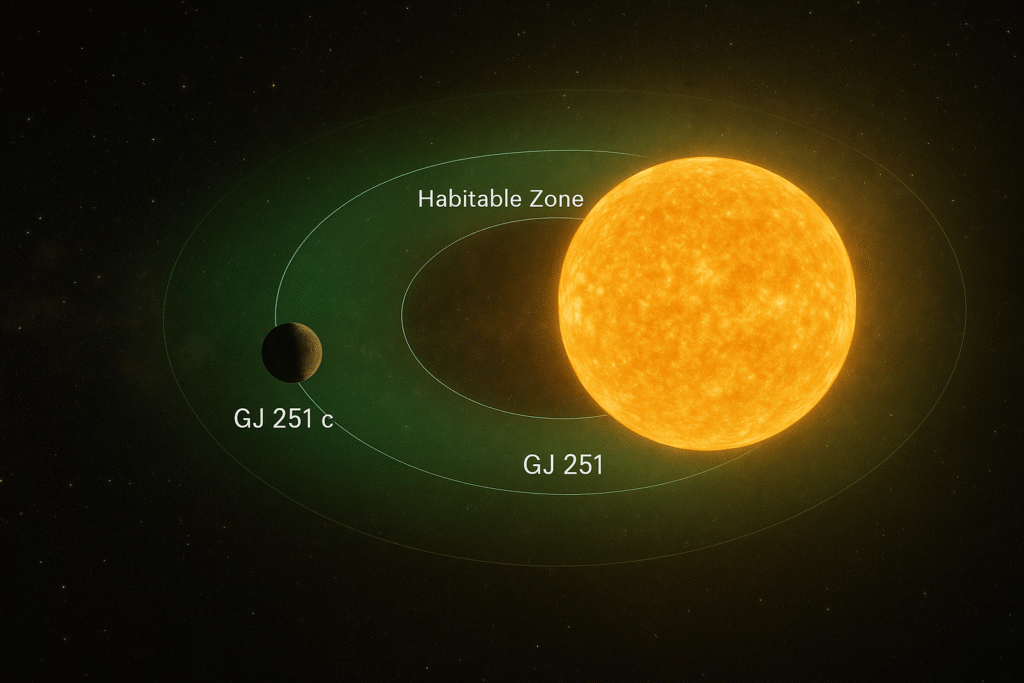

A team of astronomers at the University of California, Irvine has identified a promising new exoplanet located within the habitable zone of its star — a region where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist. The planet, designated GJ 251 c, lies only 18 light-years from Earth, making it one of the nearest potentially habitable worlds ever detected and a prime target for future direct-imaging telescopes.

The findings, published in The Astronomical Journal, describe GJ 251 c as a rocky super-Earth, several times more massive than our planet but similar in overall composition. Because liquid water is considered essential for all known life, its position in the star’s temperate zone makes it an especially important discovery.

A Rare Opportunity in the Solar Neighborhood

“We have found so many exoplanets at this point that discovering a new one is not such a big deal,” said co-author Paul Robertson, associate professor of physics and astronomy at UC Irvine. “What makes this one stand out is its proximity. At only about 18 light-years away, it’s cosmically next door.”

That short distance opens the door to unprecedented follow-up observations. Scientists expect that the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) — currently under development — will have the resolution necessary to directly image the planet, analyze its atmosphere, and potentially search for signs of water.

“TMT will be the only telescope with sufficient resolution to image exoplanets like this one,” said Corey Beard, lead author of the study. “Smaller telescopes simply cannot achieve this level of detail.”

A Planet Around an Active M-Dwarf Star

GJ 251 c orbits an M-dwarf star, the most abundant type of star in the Milky Way. While common, M-dwarfs pose unique challenges: their magnetic activity, including starspots and powerful flares, can mimic or obscure the faint signals astronomers rely on to detect planets.

To overcome this, the team used two of the most precise radial-velocity instruments available:

- HPF (Habitable-zone Planet Finder)

- NEID spectrograph

Robertson helped develop both systems. By tracking tiny shifts in the star’s light — caused by the gravitational “tug” of an orbiting planet — researchers confirmed the presence of GJ 251 c. HPF’s near-infrared observations were especially important because M-dwarf noise is weaker in that part of the spectrum.

“The instruments allow us to separate the planet’s signal from the star’s activity,” Beard noted. “But confirming the planet’s properties will require next-generation telescopes like TMT.”

High-Resolution Tools Reveal a Subtle, Promising Signal

The team modeled the star’s light variations using statistical tools designed to isolate true orbital motion from stellar noise. Their analyses produced a strong radial-velocity signal: consistent, periodic, and aligned with expectations for a rocky planet in the habitable zone.

Despite the strong evidence, the team labels GJ 251 c a planet candidate until direct imaging confirms its mass and atmospheric characteristics.

“We’re right at the edge of what current technology can do,” Beard said. “This system represents the frontier of detection limits.”

A Target for the Future of Exoplanet Science

Because of its distance and position in the habitable zone, GJ 251 c is expected to be a key target for future missions aimed at finding biomarkers — chemical signatures in a planet’s atmosphere that could indicate biological processes.

The discovery also serves as a benchmark for evaluating the limits of ground-based radial-velocity instruments and motivates deeper study of M-dwarf planetary systems.

“GJ 251 c is exactly the kind of target that pushes the community toward the next generation of telescopes,” Robertson said. “It is close, potentially rocky, and likely temperate. It’s everything we look for in the search for life beyond Earth.”

The study involved researchers at UC Irvine, UCLA, Penn State University, the University of the Netherlands, and the University of Colorado Boulder. Funding came from the National Science Foundation and NASA’s NN-EXPLORE and ICAR programs.