By Harshit

WASHINGTON, JANUARY 14, 2026 —

Digital technology is often discussed in terms of speed, convenience, and innovation. Cloud services, artificial intelligence, streaming platforms, and online communication tools are typically framed as intangible or “virtual.” Yet behind this digital world lies a rapidly growing physical footprint—one that is increasingly shaping scientific research, energy planning, and technology policy in the United States.

As 2026 begins, scientists, engineers, and policymakers are paying closer attention to the rising energy demands created by modern digital systems. The issue is not about a single technology, but about the cumulative impact of continuous computing, data storage, and network activity that now underpin everyday life.

Digital Services Depend on Physical Systems

Every digital action—sending an email, streaming a video, processing an online payment—relies on physical infrastructure. Servers, networking equipment, cooling systems, and power supplies operate around the clock to support digital services.

Unlike traditional industrial activity, which may fluctuate with working hours or production cycles, digital infrastructure runs continuously. This constant demand places unique pressure on energy systems, particularly as digital usage continues to grow across households, businesses, and government services.

Scientists emphasize that digital efficiency gains at the device level do not always translate into lower overall energy use, because total demand continues to rise.

The Growth of Always-On Computing

One defining feature of modern technology is that it is always active. Cloud platforms support applications that run continuously, while real-time data processing has become standard in fields ranging from finance to healthcare.

Artificial intelligence workloads, in particular, require sustained computational power. Training and operating large-scale models involves intensive processing that consumes significant electricity over long periods.

This shift toward always-on computing distinguishes today’s digital economy from earlier eras, when computing demand was more episodic and localized.

Energy Use Is Becoming a Scientific Measurement Problem

Understanding the energy impact of digital technology is not straightforward. Energy use is distributed across many facilities and systems, making it difficult to measure in a single metric.

Scientists study not only electricity consumption, but also secondary effects such as heat generation, cooling requirements, and transmission losses. In some cases, energy use is influenced by geographic factors, including climate and proximity to power sources.

This complexity has led researchers to treat digital energy demand as a systems-level challenge rather than a narrow engineering issue.

Strain on Power Infrastructure

As digital demand grows, its interaction with the power grid has become a subject of closer scrutiny. In certain regions, clusters of technology infrastructure represent a significant share of local electricity consumption.

Utilities must ensure reliability while balancing competing demands from households, industry, and essential services. Sudden spikes in digital load or long-term growth can require upgrades to generation, transmission, and distribution systems.

Energy planners increasingly incorporate digital infrastructure into long-term forecasts, recognizing that technology growth is now a core driver of electricity demand.

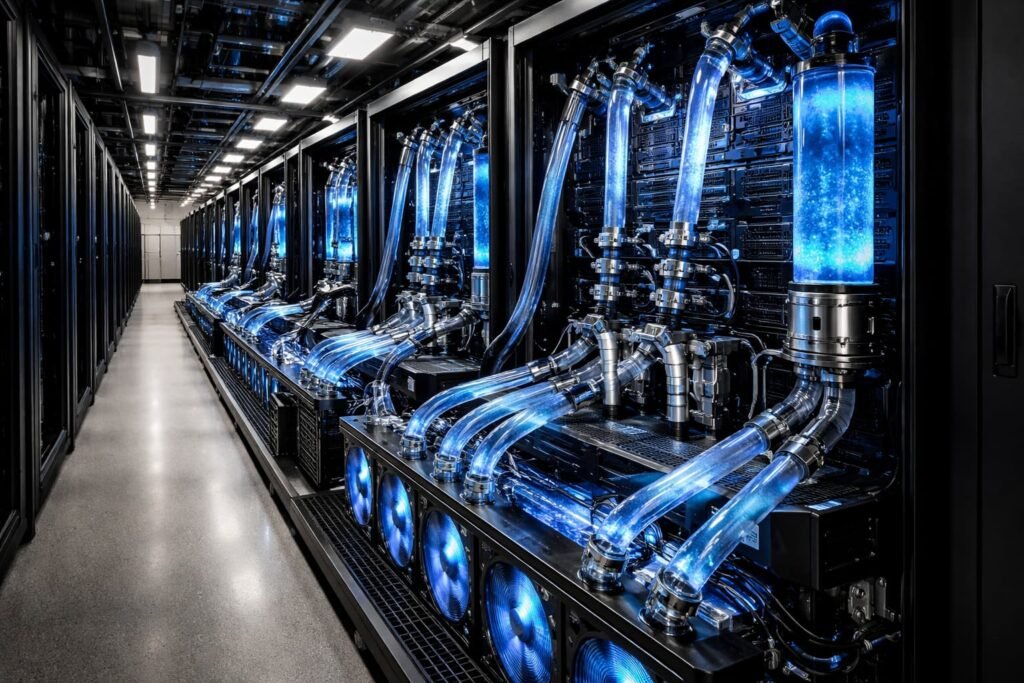

Cooling and Thermal Management

Beyond electricity, digital systems generate heat that must be managed carefully. Cooling is essential to prevent equipment failure and maintain performance.

Cooling methods vary widely, from air-based systems to liquid cooling technologies. Each approach carries trade-offs in efficiency, cost, and environmental impact.

Scientists and engineers continue to research ways to improve thermal management, recognizing that cooling can account for a substantial share of a facility’s total energy use.

Why This Is Becoming a Policy Issue

The scientific challenges surrounding digital energy use increasingly intersect with public policy. Questions arise about grid resilience, energy efficiency standards, and long-term sustainability.

Agencies such as the U.S. Department of Energy support research into advanced computing efficiency and energy systems, reflecting recognition that digital infrastructure is now a national concern.

Policymakers are not focused on limiting technology use, but on ensuring that growth aligns with energy capacity and reliability. This requires coordination across technology companies, utilities, and regulators.

The Trade-Off Between Innovation and Consumption

One of the central tensions in this discussion is the trade-off between innovation and resource use. Digital tools enable productivity gains, scientific discovery, and economic growth. At the same time, their physical demands are real and growing.

Scientists emphasize that the goal is not to halt innovation, but to understand its full cost and design systems accordingly. This includes improving hardware efficiency, optimizing software workloads, and integrating digital infrastructure more closely with energy planning.

Efficiency gains matter, but so does transparency about total demand.

Public Awareness Remains Limited

Despite its significance, digital energy use remains largely invisible to the public. Consumers rarely see the energy footprint of online services, which can make the issue feel abstract.

Researchers argue that greater awareness could support more informed decision-making, both at the individual and institutional level. Understanding that digital convenience carries physical costs may influence how systems are designed and managed.

However, experts caution against oversimplification. Digital services also reduce energy use in other areas, such as transportation and paper-based systems. The net impact depends on context and design.

Looking Ahead Through 2026

As the year unfolds, digital energy demand is expected to remain a growing focus of scientific study and policy discussion. The challenge lies in managing growth without compromising reliability or sustainability.

In 2026, digital technology is no longer just a software story. It is an infrastructure story, an energy story, and increasingly, a scientific one. How the United States navigates this challenge will shape the resilience of both its digital systems and its energy networks for years to come.

Understanding the physical realities behind digital innovation is a necessary step toward building a technology ecosystem that is not only powerful, but sustainable.