By Harshit

NEW YORK, DECEMBER 9 —

A decade after humanity first detected gravitational waves, scientists have now recorded the clearest black hole merger signal ever observed, reinforcing foundational theories proposed by Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking.

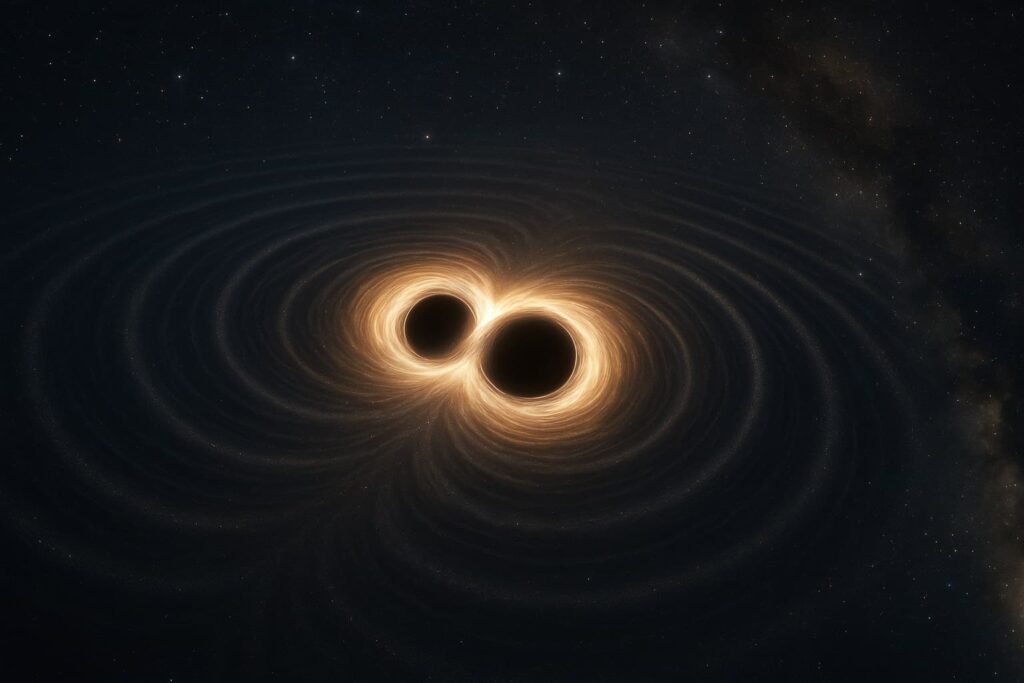

The signal, known as GW250114, was detected in January 2025 by the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) collaboration, using upgraded gravitational-wave observatories in the United States and abroad. The event involved the collision and merger of two black holes, producing ripples in spacetime that reached Earth after traveling billions of light-years.

According to researchers, the unprecedented clarity of this signal allowed them to confirm with high precision that black holes obey two long-standing predictions: that their total surface area never shrinks after a merger, and that newly formed black holes vibrate in a distinct, predictable way described by general relativity.

“This signal puts some of our most fundamental ideas about black holes to the test — and they passed,” said astronomer Maximiliano Isi of Columbia University, a member of the LVK collaboration.

A Sharper Look at a Violent Cosmic Event

Gravitational waves were first directly observed in 2015, when LIGO detected spacetime distortions from a black hole merger. While that discovery confirmed Einstein’s 100-year-old theory, data quality at the time limited deeper tests of black hole physics.

Since then, detector sensitivity has improved dramatically. The GW250114 event was recorded almost four times more clearly than the first detection, allowing scientists to isolate subtle features in the gravitational-wave signal that were previously hidden by noise.

This level of precision enabled researchers to examine not only the violent inspiral and collision but also the “ringdown” phase — the brief period after the merger when the newly formed black hole settles into its final shape.

Confirming Hawking’s Area Theorem

In 1971, physicist Stephen Hawking proposed that the surface area of a black hole’s event horizon — the point beyond which nothing can escape — can never decrease. Known as the black hole area theorem, the idea is rooted in Einstein’s equations and is often compared to a law of thermodynamics for black holes.

Earlier gravitational-wave observations provided tentative confirmation of this principle. The GW250114 signal, however, offers the strongest observational evidence yet that the total event horizon area after a merger is always equal to or greater than the combined areas of the original black holes.

The confirmation was possible because data from both U.S. LIGO detectors — located in Washington state and Louisiana — were used simultaneously, reducing uncertainty and boosting confidence in the measurement.

Listening to a Black Hole Ring

Beyond confirming Hawking’s prediction, researchers also analyzed the vibrations produced after the merger. Much like a struck bell, a newly formed black hole emits gravitational waves at specific frequencies as it stabilizes.

These vibrations revealed that the final object closely matches a Kerr black hole, a rotating solution to Einstein’s equations developed by mathematician Roy Kerr in the 1960s.

Physicists have long assumed all astrophysical black holes follow Kerr’s model, but direct observational proof has been elusive. By studying the detailed structure of the ringdown signal in GW250114, scientists were able to measure the black hole’s mass and spin with exceptional accuracy.

The results showed no deviations from Einstein’s predictions, providing the clearest confirmation to date that real black holes behave exactly as general relativity describes.

A New Era for Gravitational Astronomy

The findings mark a major milestone in gravitational-wave science and hint at even deeper tests to come. Over the next decade, planned upgrades to existing detectors — and the addition of next-generation observatories — are expected to further sharpen humanity’s view of the most extreme objects in the universe.

As instruments become more sensitive, scientists hope to detect subtle effects that could reveal new physics beyond Einstein’s theory or provide insights into how gravity behaves at its limits.

“For the first time, we’re not just detecting black hole mergers — we’re using them as precision laboratories,” Isi said. “This is only the beginning.”