By Harshit

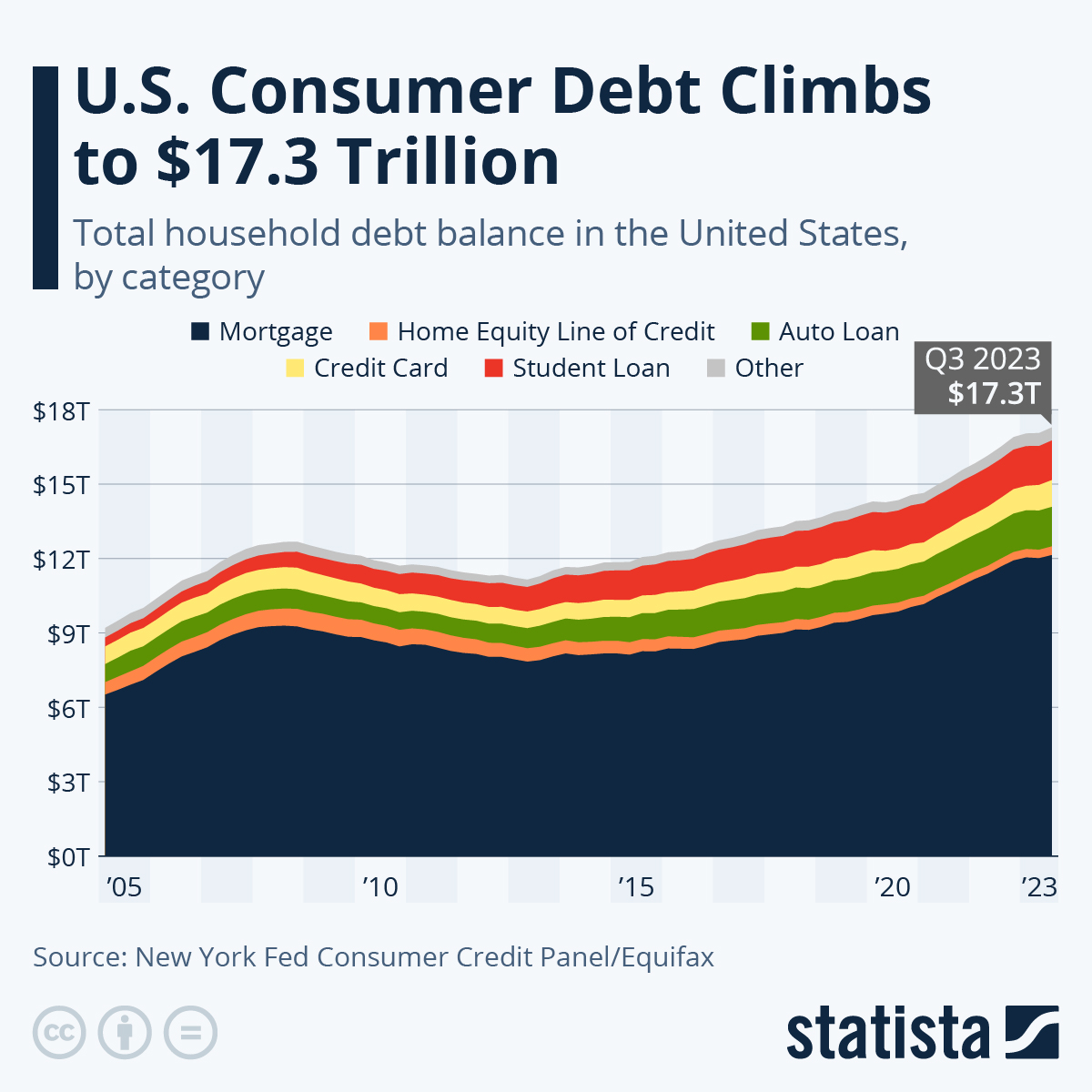

WASHINGTON, JANUARY 20 — The U.S. economy has defied repeated recession forecasts, supported by steady employment and resilient consumer activity. Yet beneath this surface stability lies a growing vulnerability that economists, lenders, and policymakers are watching closely in 2026: rising household debt.

Unlike previous cycles driven primarily by corporate leverage or government borrowing, today’s risk is increasingly concentrated at the household level—where credit dependence is quietly expanding as costs remain high and savings thin.

Debt Is Rising Even as Inflation Cools

Although inflation has eased from its peak, the price level across key household expenses remains elevated. Housing, insurance, healthcare, education, and transportation continue to consume a larger share of monthly income than they did before 2020.

To bridge the gap, many Americans are relying more heavily on credit. Credit card balances have grown steadily, auto loan terms have lengthened, and personal loans are increasingly used to manage routine expenses rather than emergencies.

This trend does not yet signal distress—but it reflects growing financial strain.

Higher Interest Rates Change the Math

What makes today’s debt environment particularly risky is the cost of servicing it. Interest rates remain structurally higher than in the previous decade, meaning households are paying more just to carry existing balances.

Minimum payments are rising, and variable-rate debt is absorbing income that might otherwise support consumption or savings. For many families, debt is no longer a temporary bridge—it is becoming a persistent obligation.

Why Delinquencies Matter More Than Defaults

So far, widespread defaults have not materialized. Instead, early warning signs are appearing in the form of rising late payments, increased reliance on balance transfers, and reduced discretionary spending.

These indicators matter because they often precede sharper economic slowdowns. When households redirect income toward debt servicing, spending slows—especially in retail, travel, and discretionary services.

The risk is not an immediate collapse, but a gradual erosion of consumer momentum.

The Uneven Burden of Debt

Household debt growth is not evenly distributed. Higher-income households often carry debt strategically, using fixed-rate mortgages and manageable leverage. Lower- and middle-income households are more exposed to high-interest credit cards and short-term loans.

This divergence increases economic inequality and makes aggregate data misleading. Overall debt levels may appear manageable, while financial stress intensifies in specific segments of the population.

Housing and Auto Loans Add Pressure

Mortgage debt remains relatively stable due to fixed-rate loans locked in during earlier years. However, new homebuyers in 2025 and 2026 are entering the market at much higher rates, increasing monthly payment burdens.

Auto loans present an even greater challenge. Vehicle prices remain high, loan terms are extended, and negative equity is becoming more common—especially among lower-income borrowers.

Why This Matters for the Broader Economy

Consumer spending accounts for roughly two-thirds of U.S. economic activity. Rising household debt does not automatically lead to recession, but it limits growth potential and increases vulnerability to shocks.

If job growth slows or unexpected expenses arise, highly leveraged households have less flexibility to absorb stress—making the economy more sensitive to disruptions.

Policy Limits and Trade-Offs

Policymakers face difficult trade-offs. Lowering interest rates too quickly risks reigniting inflation, while maintaining restrictive conditions prolongs household pressure. Fiscal relief is constrained by budget realities, leaving limited room for broad intervention.

As a result, much of the adjustment is falling on households themselves.

A Slow-Burning Risk

Household debt is not the headline crisis of 2026—but it may be the most consequential. Its effects accumulate quietly, shaping spending behavior, economic confidence, and long-term growth.

The U.S. economy remains resilient, but its foundation increasingly depends on how well households manage rising financial obligations in a high-cost environment.