By Harshit

NEW YORK, DECEMBER 23 —

For decades, health in the United States has been measured by how long people live. Today, that standard is no longer enough.

Americans are living longer than previous generations, but many of those extra years are marked by chronic disease, limited mobility, and declining independence. Public health researchers describe this growing divide as the “healthspan gap” — the years a person lives in poor health at the end of life. Current estimates suggest the average American spends nearly a decade managing preventable conditions rather than enjoying good health.

As the country moves into 2026, medical consensus is increasingly clear: closing this gap depends less on aggressive medical treatment and more on improving metabolic health.

What Metabolic Health Really Means

Metabolic health refers to how efficiently the body processes energy, regulates blood sugar, manages fat storage, and controls inflammation. It is not the same as body weight.

A person can be thin and metabolically unhealthy, or overweight and metabolically stable. What matters is how the body functions internally.

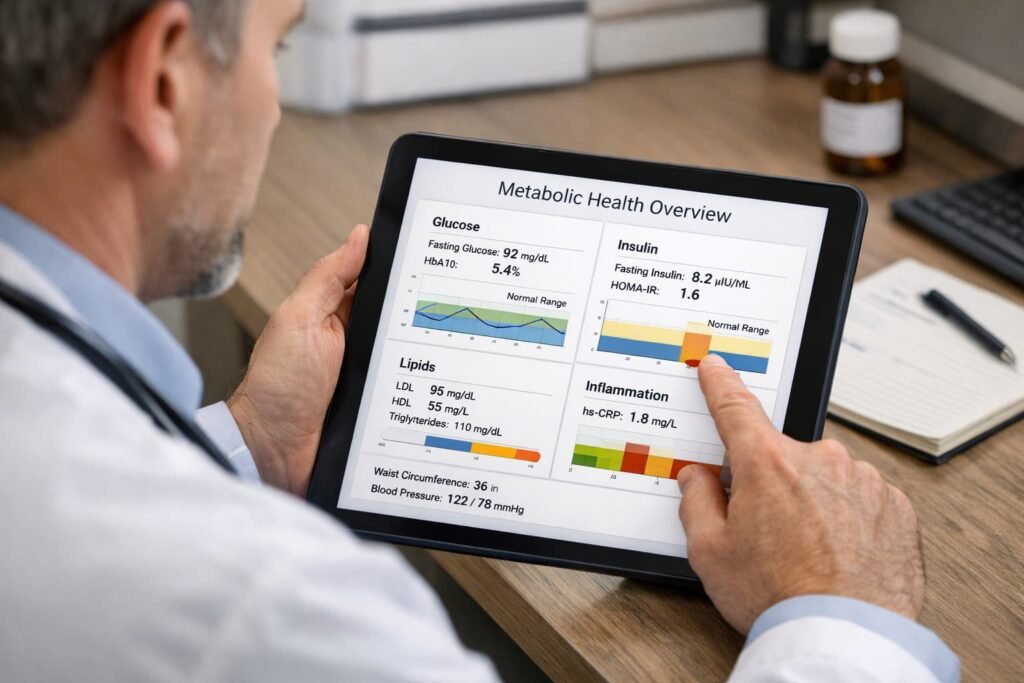

Clinicians generally assess metabolic health using five core markers: waist circumference, fasting blood glucose, blood pressure, triglycerides, and HDL (“good”) cholesterol. When three or more of these markers fall outside healthy ranges, a person is considered to have metabolic syndrome — a condition strongly linked to heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and early mortality.

Recent clinical guidance has also highlighted the triglyceride-to-HDL ratio as a particularly useful indicator. A ratio below 2.0 suggests good insulin sensitivity, while higher values point toward metabolic dysfunction even when standard cholesterol numbers appear “normal.”

Why Metabolic Dysfunction Is So Common

The rise in metabolic disease has been swift. In 1980, obesity and type 2 diabetes were relatively uncommon. Today, more than 40% of U.S. adults live with obesity, and roughly one in three has some degree of insulin resistance.

Experts increasingly agree that this trend cannot be explained by personal behavior alone. Environmental factors — including ultra-processed foods, constant sedentary time, chronic stress, sleep deprivation, and exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals — have reshaped how human metabolism functions.

The modern lifestyle often keeps insulin elevated throughout the day, leaving the body in a constant fat-storage mode while promoting inflammation and cellular damage.

Nutrition Has Shifted From Restriction to Stability

The old model of dieting — extreme calorie restriction or rigid food rules — has largely failed. Most people regain lost weight within five years, often with additional metabolic damage.

Current nutritional science emphasizes glucose stability rather than weight loss. The goal is to prevent repeated spikes in blood sugar that drive insulin resistance over time.

Fiber plays a central role. Despite longstanding recommendations, roughly 90% of Americans do not consume enough fiber. Fiber slows digestion, feeds beneficial gut bacteria, and helps regulate blood sugar and cholesterol.

Protein distribution has also gained attention. Eating protein earlier in a meal has been shown to reduce post-meal glucose spikes and improve satiety. Most adults benefit from higher daily protein intake than previously recommended, especially to preserve muscle mass with age.

Added sugar remains a major concern. While federal guidelines allow up to 10% of daily calories from added sugar, mounting evidence suggests that staying below 25 grams per day offers better protection against fatty liver disease and metabolic dysfunction.

Exercise Is Now About Metabolic Efficiency

Exercise is no longer viewed simply as a way to burn calories. Instead, muscle is understood as a metabolic organ that helps regulate blood sugar and inflammation.

Steady aerobic exercise — often referred to as “Zone 2” training — has emerged as a cornerstone of metabolic health. This level of effort improves mitochondrial function, allowing cells to burn fat more efficiently and recover faster from metabolic stress.

Strength training is equally critical. Age-related muscle loss is a major driver of insulin resistance and frailty. Even modest resistance training two to three times per week significantly improves glucose control and reduces long-term disease risk.

Equally important is reducing sedentary time. Research shows that breaking up long periods of sitting with brief movement can substantially lower post-meal blood sugar and insulin levels, even in people who exercise regularly.

Sleep Is a Metabolic Regulator, Not a Luxury

Sleep is often overlooked in discussions of metabolic health, yet it may be one of the most powerful influences.

Poor sleep disrupts hormonal balance, raises cortisol, impairs insulin sensitivity, and increases appetite for high-calorie foods. Even a single night of insufficient sleep can push the body into a temporary prediabetic state.

Circadian rhythm also matters. Late-night eating and exposure to bright screens after sunset interfere with the body’s internal clock, reducing sleep quality and metabolic efficiency. Consistent sleep timing, morning light exposure, and avoiding food late at night all support healthier glucose regulation.

Technology Is Changing Awareness — Not Replacing Fundamentals

Health technology has matured rapidly. Wearables now track heart rate variability, sleep stages, and recovery metrics. Continuous glucose monitors, once reserved for diabetics, are increasingly used by non-diabetics to understand personal responses to food and stress.

These tools have revealed a critical truth: metabolic responses are highly individual. The same food can cause dramatically different glucose reactions in different people.

Still, experts caution that technology should guide behavior, not create anxiety. The fundamentals remain unchanged: diet quality, movement, sleep, and consistency.

A Practical Path Forward

Closing the healthspan gap does not require extreme interventions for most people. It requires sustained attention to basic biology.

Knowing personal metabolic markers, prioritizing protein and fiber, limiting added sugar, building muscle, moving daily, and protecting sleep can dramatically reduce the risk of chronic disease.

Metabolic health is not a short-term project. It is a lifelong practice. But the payoff is substantial: fewer years lost to illness, greater independence with age, and a longer life spent in good health rather than medical care.

As America looks toward 2026, the message from science is clear — longevity is no longer just about surviving longer. It is about living better, longer.