By Harshit

MONTREAL, DECEMBER 22, 2025

A new study led by researchers at McGill University is challenging one of neuroscience’s long-held assumptions about dopamine and movement. The findings suggest that dopamine does not directly dictate how fast or forcefully movements are executed, but instead provides the baseline conditions that make movement possible at all.

Published in Nature Neuroscience, the research offers a shift in how scientists understand both normal motor control and the biological basis of Parkinson’s disease—with important implications for treatment strategies.

“Our findings suggest we should rethink dopamine’s role in movement,” said senior author Nicolas Tritsch, assistant professor in McGill’s Department of Psychiatry and researcher at the Douglas Research Centre. “Restoring dopamine to a normal level may be sufficient to improve movement. That could simplify how we think about Parkinson’s treatment.”

Dopamine’s Role in Parkinson’s Disease

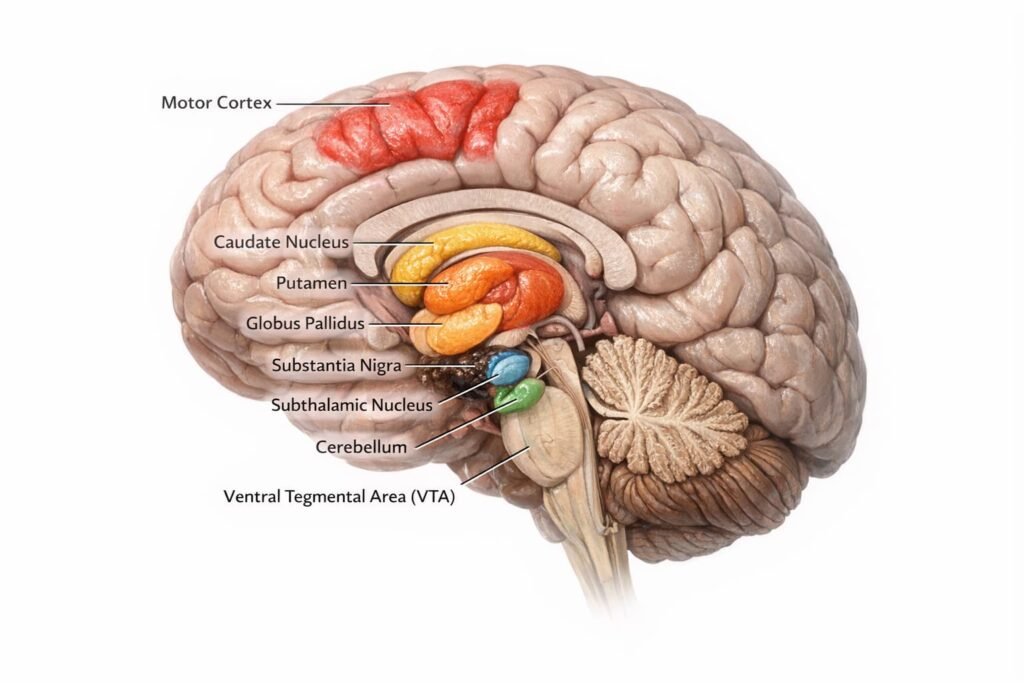

Dopamine is essential for coordinated movement and motivation. In Parkinson’s disease, dopamine-producing neurons gradually degenerate, leading to symptoms such as slowed movement, rigidity, tremor, and impaired balance.

For decades, scientists believed dopamine directly controlled motor vigor—the speed and force of movement. This view was reinforced by newer technologies that detected brief dopamine surges occurring during movement, suggesting the neurotransmitter acted as a real-time movement regulator.

Levodopa, the most widely prescribed Parkinson’s medication, restores dopamine levels and dramatically improves symptoms. However, exactly why it works so well has remained unclear.

The new study suggests that dopamine’s role has been misunderstood.

Dopamine as a Support System, Not a Throttle

Rather than acting as a moment-by-moment controller, dopamine appears to function more like a background enabler of movement.

“Dopamine is less like a gas pedal and more like engine oil,” Tritsch explained. “It’s necessary for the system to function, but it doesn’t determine how fast each movement happens.”

This analogy captures the study’s central insight: dopamine creates the neural environment that allows movement circuits to operate, but it does not fine-tune individual actions as they unfold.

Testing Dopamine in Real Time

To examine dopamine’s role directly, researchers conducted experiments in mice trained to press a weighted lever. Using optogenetics—a technique that uses light to control specific neurons—the team was able to rapidly turn dopamine neurons on or off while the animals were moving.

If dopamine bursts controlled movement vigor, altering dopamine levels at the exact moment of action should have changed how quickly or forcefully the mice pressed the lever. It did not.

Movement speed and strength remained unchanged when dopamine activity was manipulated mid-action.

Why Levodopa Still Works

When the researchers administered levodopa, they observed clear improvements in movement—but for a different reason than previously assumed.

Levodopa increased overall dopamine tone in the brain rather than restoring rapid dopamine spikes. The results suggest that levodopa works by re-establishing a permissive baseline that allows motor circuits to function properly, not by fine-tuning movement intensity.

This distinction helps explain why Parkinson’s symptoms improve even though dopamine signaling remains imperfect.

Implications for Future Parkinson’s Therapies

More than 110,000 Canadians are currently living with Parkinson’s disease, and that number is expected to more than double by 2050 as populations age.

The study’s findings suggest future therapies may benefit from prioritizing stable dopamine availability rather than targeting fast, transient dopamine signals. This could help guide the design of treatments with fewer side effects and more consistent benefits.

The work also invites a re-evaluation of older dopamine-based therapies, such as dopamine receptor agonists, which can improve symptoms but often affect large brain regions and cause unwanted effects.

A clearer understanding of dopamine’s true role may enable more precise, safer interventions.

A Shift in How Movement Is Understood

Beyond Parkinson’s disease, the findings have broader implications for neuroscience. They challenge a simple cause-and-effect view of neurotransmitters and emphasize the importance of background brain states in shaping behavior.

Rather than acting as a command signal, dopamine appears to define whether movement is possible—not how it is executed moment to moment.

About the Study

The study, titled “Subsecond dopamine fluctuations do not specify the vigor of ongoing actions,” was authored by Haixin Liu, Nicolas Tritsch, and colleagues.

Funding was provided by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund through McGill University’s Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative, as well as the Fonds de Recherche du Québec.