By Harshit

Riverside, California | November 19, 2025 | 03:15 AM PST

A new study by researchers at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) has found that chronic exposure to microplastics—tiny plastic fragments that contaminate food, water, and air—may accelerate the development of atherosclerosis, the artery-narrowing condition linked to heart attacks and strokes.

The research, published in Environment International, revealed that male mice exposed to realistic levels of microplastics developed significantly more arterial plaque than females, suggesting a sex-specific vulnerability in how the body responds to these pollutants.

“Our findings fit into a broader pattern seen in cardiovascular research, where males and females often respond differently,” said Dr. Changcheng Zhou, professor of biomedical sciences at the UCR School of Medicine and the study’s senior author. “Although the precise mechanism isn’t yet known, factors like sex chromosomes and hormones—particularly estrogen—may play a protective role.”

What Are Microplastics and Why They Matter

Microplastics are microscopic particles—usually less than 5 millimeters in size—that come from plastic packaging, synthetic fabrics, industrial waste, and even cosmetic products. They have been detected virtually everywhere, from drinking water and seafood to the human bloodstream and organs.

Recent clinical evidence has identified microplastics inside atherosclerotic plaques in humans, raising concerns that they could directly contribute to cardiovascular disease rather than simply being a byproduct of environmental contamination.

“It’s nearly impossible to avoid microplastics completely,” Zhou noted. “But the best strategy is to limit plastic exposure—reduce single-use plastics, avoid highly processed foods, and use glass or metal containers whenever possible.”

How the Study Was Conducted

To explore whether microplastics could actively cause artery damage, Zhou’s team used LDLR-deficient mice, a common model for studying atherosclerosis. Both male and female mice were placed on a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet, mimicking a healthy human diet.

Over a nine-week period, the researchers administered microplastics daily—approximately 10 milligrams per kilogram of body weight—reflecting realistic environmental exposure through food and water.

At the end of the study, the team measured the development of plaque in major arteries.

Microplastics Worsened Plaque in Males Only

The results were striking:

- Male mice exposed to microplastics developed 63% more plaque in the aortic root (the part of the aorta nearest the heart) and an astonishing 624% more plaque in the brachiocephalic artery, a key blood vessel in the chest.

- Female mice, however, did not show significant changes in plaque formation under the same conditions.

Importantly, the microplastics did not affect body weight or cholesterol levels in either sex, meaning traditional cardiovascular risk factors—like obesity and high lipid levels—could not explain the difference.

“We found that microplastics don’t raise cholesterol or body fat,” Zhou said. “Instead, they appear to act directly on the vascular system, particularly the cells lining the arteries.”

How Microplastics Damage Arteries

Using single-cell RNA sequencing, the researchers analyzed how microplastics affect endothelial cells, which line blood vessels and regulate blood flow and inflammation.

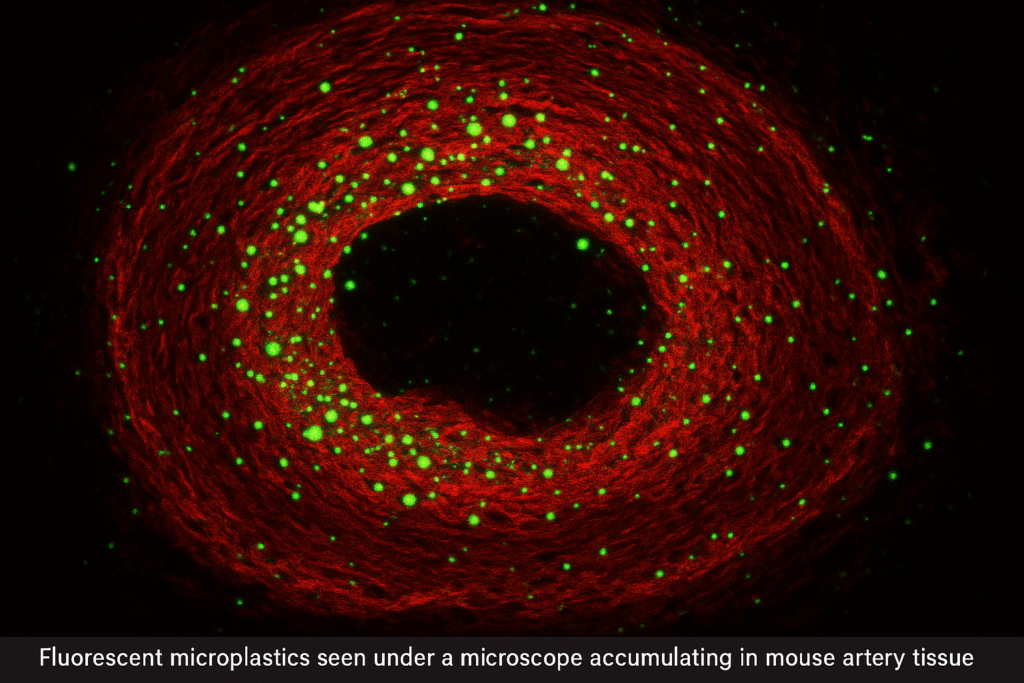

They discovered that microplastic exposure disrupted gene activity in these cells, triggering pathways linked to inflammation, oxidative stress, and plaque formation. Fluorescent microplastics were also found embedded in the arterial walls, confirming that the particles can physically enter blood vessels and accumulate inside plaques.

“Endothelial cells were the most affected by microplastic exposure,” Zhou said. “Since these cells are the first to encounter circulating particles, their dysfunction can initiate inflammation and plaque buildup.”

This cellular disruption mirrors early events in human atherosclerosis, suggesting that microplastics could act as a hidden environmental risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

A Sex-Specific Effect: Why Males Are More Vulnerable

One of the most intriguing findings was that only male mice showed worsened arterial disease. While the exact reason remains unclear, researchers believe sex hormones, particularly estrogen, may protect female arteries from inflammation and cell damage caused by microplastics.

“The surprising sex-specific effect—harming males but not females—could help uncover protective factors or mechanisms that differ between men and women,” Zhou explained.

This discovery could reshape how scientists study cardiovascular risk, emphasizing biological sex as a key variable in environmental health research.

Broader Implications for Human Health

The study adds to mounting evidence that microplastics are not inert and may directly harm human tissues. In 2024, researchers in Italy reported finding microplastics in every human artery sample tested, with higher concentrations correlating to increased heart disease risk.

Zhou’s findings suggest a causal link—not just an association—between microplastic exposure and vascular injury.

“Our study provides some of the strongest evidence so far that microplastics may directly contribute to cardiovascular disease, not just correlate with it,” Zhou said.

Next Steps: Understanding and Preventing Microplastic Damage

Zhou and his collaborators at Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center plan to extend the work to human tissue models and investigate:

- Whether humans show similar sex-specific effects,

- How different sizes and types of microplastics (such as polystyrene vs. polyethylene) affect vascular cells, and

- What molecular pathways link microplastic exposure to endothelial dysfunction.

The research, partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), could ultimately inform public health policies and lead to new cardiovascular therapies targeting inflammation caused by environmental pollutants.

“As microplastic pollution continues to rise worldwide, understanding its impact on human health—especially heart disease—is becoming more urgent than ever,” Zhou emphasized.