By Harshit

Salt Lake City, Utah | November 18, 2025 | 10:45 AM MST

In a groundbreaking study that could transform the understanding of anxiety disorders, scientists at the University of Utah have discovered two distinct types of brain immune cells that act as opposing regulators of anxious behavior — functioning like an internal “accelerator” and “brake.”

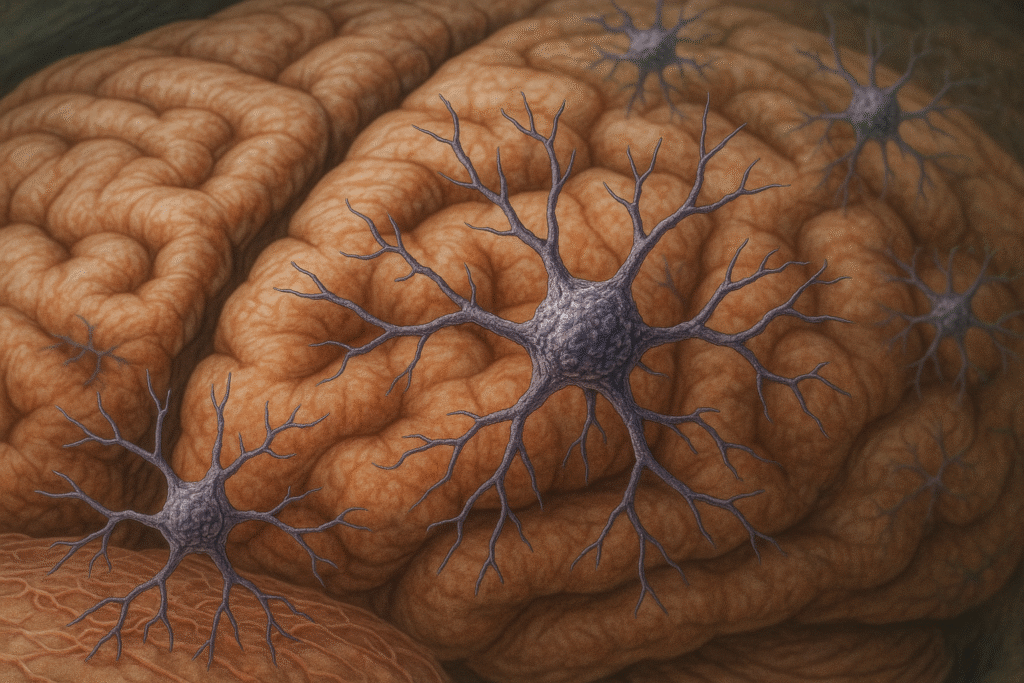

Published in Molecular Psychiatry, the research identifies specific subsets of microglia — immune cells that act as the brain’s first line of defense — as central to controlling anxiety. The findings challenge long-held beliefs that anxiety is driven primarily by neurons, which transmit electrical signals across the nervous system.

“This is a paradigm shift,” said Dr. Donn Van Deren, lead author and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, who conducted the research during his time at University of Utah Health. “It shows that when the brain’s immune system is not healthy, it can directly lead to neuropsychiatric disorders like anxiety.”

Microglia Take Center Stage in Anxiety Regulation

Traditionally, scientists believed that neurons — not immune cells — were responsible for anxiety responses. But previous experiments hinted that microglia might influence behavior.

When researchers disrupted a subset of microglia known as Hoxb8 microglia, mice began showing signs of anxiety — incessantly grooming themselves and avoiding open spaces. Surprisingly, when they suppressed all microglia in the brain, those anxious behaviors disappeared, suggesting the existence of two opposing groups of microglia: one promoting anxiety and another reducing it.

“The results didn’t make sense at first,” Van Deren explained. “Blocking one group made mice anxious, but blocking them all made them calm. That told us there had to be two populations working in opposite ways.”

The Brain’s “Accelerator” and “Brake” for Anxiety

To unravel the puzzle, researchers designed an elegant experiment. They used genetically modified mice that lacked microglia entirely and then transplanted different microglial types to observe how each influenced behavior.

The results were striking:

- Mice that received only non-Hoxb8 microglia showed extreme anxiety, repeatedly grooming and avoiding light or open areas — behaviors mirroring human anxiety symptoms.

- Mice transplanted with only Hoxb8 microglia, however, remained calm and balanced.

- Mice given both types exhibited normal behavior, suggesting the two populations naturally balance each other to maintain healthy anxiety levels.

“These two populations of microglia have opposite roles,” said Dr. Mario Capecchi, Nobel laureate and senior author of the study. “Together, they fine-tune the appropriate level of anxiety depending on what’s happening in the environment.”

Capecchi compared the system to a car: non-Hoxb8 microglia act as the gas pedal, increasing anxiety responses, while Hoxb8 microglia serve as the brake, preventing the system from overreacting.

Why the Findings Are a Major Breakthrough

Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health conditions in the U.S., affecting roughly one in five adults each year. Despite their prevalence, the biological roots of anxiety have remained elusive — and most current treatments, such as antidepressants and anxiolytics, target neurons, not immune cells.

The Utah team’s discovery represents a major step forward in linking neuroimmunology — the interaction between the brain and immune system — with psychiatric illness.

“Humans also have these two populations of microglia,” Capecchi said. “If we can find ways to restore the proper balance between them, we could potentially correct anxiety at its biological source.”

A New Path for Future Treatments

The implications of this research go far beyond basic science. It opens the door to new therapies that target microglia activity instead of neural signaling — a completely different biological approach to mental health treatment.

“We’re far from the therapeutic side,” Van Deren cautioned. “But someday, we might be able to design drugs or immunotherapies that selectively strengthen the ‘braking’ microglia or suppress the ‘accelerator’ microglia.”

Such therapies could be especially valuable for patients who do not respond to current medications, which often come with side effects and take weeks to work.

Moreover, microglia are involved not only in anxiety but also in depression, autism, Alzheimer’s disease, and chronic pain. Understanding how they influence emotional behavior could therefore have far-reaching consequences for multiple brain disorders.

Microglia: More Than Brain Housekeepers

For decades, microglia were viewed primarily as support cells — responsible for cleaning up dead neurons and defending against infection. However, recent discoveries have revealed that they also play active roles in synaptic pruning, neural development, and behavioral regulation.

This latest work adds another layer of complexity, showing that microglia can directly modulate emotional states by controlling anxiety circuits in the brain.

“Microglia are emerging as central players in mental health,” Capecchi noted. “They are not just the janitors of the brain — they are part of its emotional decision-making machinery.”

Looking Ahead: Toward Personalized Neuroimmune Medicine

The study underscores how psychiatric disorders might stem not only from chemical imbalances but also from immune dysfunction within the brain. By identifying molecular differences between the two microglial subtypes, researchers hope to develop biomarkers to predict anxiety vulnerability or treatment response in patients.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute of Mental Health, as well as the Dauten Family Foundation and the University of Utah Flow Cytometry Facility.

“This work brings us closer to understanding anxiety at the cellular level,” Capecchi concluded. “It gives us a roadmap for developing treatments that are more precise, more effective, and potentially free from the side effects of current psychiatric drugs.”