By Harshit

STANFORD, Calif., Nov. 17 —

In a groundbreaking advance for blindness treatment, scientists from Stanford Medicine and a network of international research partners have partially restored sight to patients suffering from an advanced form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) — using a tiny wireless retinal chip and smart glasses.

In the yearlong clinical trial, published on Oct. 20 in the New England Journal of Medicine, 27 of 32 participants regained the ability to read — a milestone once thought impossible for individuals who had lost central vision.

With the help of digital features such as zoom, contrast enhancement, and brightness adjustment, some participants achieved visual clarity comparable to 20/42 vision, marking one of the most successful demonstrations of artificial vision to date.

A New Era in Functional Vision

The implant, known as PRIMA, was developed by a team at Stanford Medicine led by Daniel Palanker, PhD, professor of ophthalmology and senior author of the study.

PRIMA represents the first prosthetic retinal system capable of restoring form vision — the ability to distinguish shapes and patterns — to individuals whose photoreceptor cells have been irreparably damaged.

“Previous prosthetic devices only provided light perception — flashes or shadows — but not recognizable shapes,” said Palanker. “We are the first to provide form vision.”

The international collaboration was co-led by José-Alain Sahel, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and Frank Holz, MD, of the University of Bonn in Germany, who served as the study’s lead author.

How the PRIMA System Works

The PRIMA system combines two key components:

- A miniature camera built into a pair of high-tech glasses.

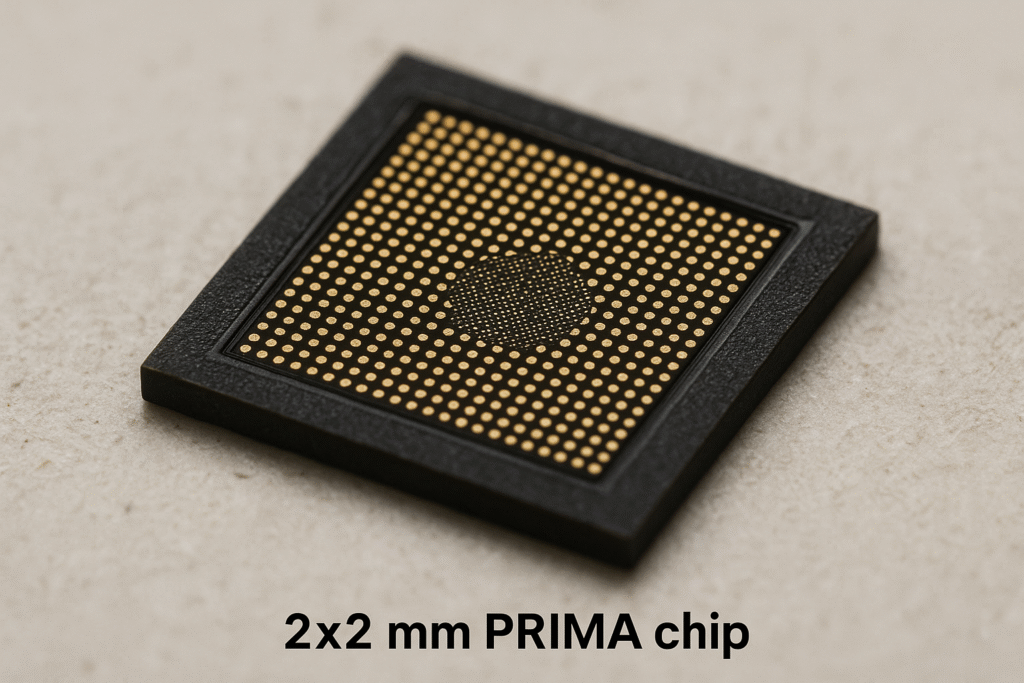

- A 2×2 millimeter photovoltaic chip implanted under the retina.

The camera captures visual scenes and transmits them as infrared light signals to the implant. The chip converts these signals into electrical impulses, stimulating the still-functioning retinal neurons to send visual information to the brain — bypassing the destroyed photoreceptors.

Because the human eye is transparent to infrared light, this wireless communication method allows the system to operate safely and efficiently without any external wiring or power source.

Palanker conceived the concept two decades ago. “I realized we could use the eye’s transparency to deliver visual data using light,” he said. “The device we imagined in 2005 now works remarkably well in patients.”

Restoring Lost Photoreceptor Function

The clinical trial focused on patients with geographic atrophy, a severe form of AMD that destroys the central retina while leaving peripheral vision intact.

Over 5 million people worldwide are affected by this condition, the leading cause of irreversible blindness among older adults.

By placing the PRIMA chip in the damaged macular region, researchers were able to replace the lost light-sensing photoreceptors with an artificial interface that communicates directly with the brain.

“The projection is done using infrared light,” Palanker explained, “because it remains invisible to healthy photoreceptors in the peripheral retina, allowing patients to use both natural and artificial vision simultaneously.”

This design enables users to blend prosthetic central vision with their remaining natural peripheral vision, dramatically improving navigation, reading, and spatial awareness.

From Light to Letters: Learning to See Again

The study enrolled 38 participants aged 60 and above who had vision worse than 20/320 in at least one eye due to advanced AMD.

Four to five weeks after the implantation surgery, patients began using their smart glasses. Some were able to recognize shapes and patterns almost immediately; others required months of visual training, much like patients adapting to cochlear implants for hearing.

After one year:

- 27 participants regained reading ability.

- 26 participants improved visual acuity by at least two lines on a standard eye chart.

- The average improvement was five lines, with one participant gaining 12 lines of clarity.

Patients reported using the device to read books, food labels, and subway signs, often magnifying text up to 12 times and adjusting contrast for clarity.

Two-thirds expressed medium to high satisfaction, emphasizing the restored sense of independence in daily life.

Managing Risks and Side Effects

The procedure was largely safe, though 19 participants experienced mild to moderate side effects, including ocular hypertension, peripheral retinal tears, and subretinal bleeding.

All complications resolved within two months, and none posed a long-term health risk.

“These are typical of intraocular procedures,” said Holz, “and they were managed effectively in every case.”

Technical Design: Wireless, Photovoltaic, and Scalable

Unlike older retinal prosthetics that required external power cables, PRIMA operates entirely wirelessly using photovoltaic technology.

Each implant contains 378 pixels, each 100 microns wide — roughly the width of a human hair. Future iterations, currently being tested in animal models, could feature pixels as small as 20 microns, providing far sharper resolution.

Palanker estimates that such advancements could enable vision approaching 20/80, and with electronic zoom, potentially 20/20.

“This is just the first generation,” he said. “As pixel density increases and glasses become sleeker, we can expect both visual quality and comfort to improve dramatically.”

The Next Frontier: Grayscale and Face Recognition

For now, PRIMA provides black-and-white vision only, but new software is under development to introduce grayscale — a vital step toward recognizing human faces and more complex visual scenes.

“Reading is number one on patients’ wish lists,” said Palanker. “Face recognition is a very close second. To achieve that, we need the full range of grayscale.”

A Global Collaboration in Vision Science

The study involved scientists and clinicians from more than a dozen institutions worldwide, including:

- University of Bonn (Germany)

- University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (U.S.)

- Hôpital Fondation A. de Rothschild (France)

- Moorfields Eye Hospital and University College London (U.K.)

- University of Rome Tor Vergata (Italy)

- University of Lübeck (Germany)

- Erasmus University Medical Center (Netherlands)

- University of Ulm (Germany)

- Science Corp. (U.S.)

- University of California, San Francisco

- University of Washington

Funding came from Science Corp., the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, and the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology.

Restoring Sight, Restoring Hope

For millions living with macular degeneration, the PRIMA implant represents a turning point — transforming what was once considered irreversible blindness into a condition that can be partially restored with technology.

While still in early stages, the results demonstrate the potential of bioelectronic vision systems to bridge the gap between biology and machine learning, between light and sight.

As Palanker summed it up:

“This is the first step toward restoring true vision — not just light perception — to those who’ve lost it. The next generation of implants will only bring us closer to natural sight.”