By Harshit | 4 October 2025 | Chongqing, China | 09:30 AM CST

In a historic first, scientists have successfully converted a donor kidney into a ‘universal’ blood type organ and transplanted it into a patient diagnosed with brain death in China. The achievement, reported in Nature Biomedical Engineering on 3 October, could transform organ transplantation by removing one of the most significant barriers to donor-recipient matching: blood type compatibility.

The Challenge of Blood Type in Transplantation

Currently, organ allocation is heavily restricted by the blood type of both donors and recipients. Blood type incompatibility leads to immediate and severe immune rejection, as the recipient’s immune system attacks donor organs carrying incompatible antigens. Antigens — A and B — are molecular markers on the surface of blood cells and tissues that trigger immune recognition. Organs with type O blood, which lack both A and B antigens, are universally compatible, but represent only a portion of available donations.

This limitation significantly contributes to transplant waiting lists, where thousands of patients worldwide die each year before a suitable organ becomes available. By converting non-O organs into type O, researchers hope to widen the donor pool and reduce mortality linked to transplant shortages.

The Enzyme-Based Conversion

The breakthrough was made possible through an enzyme first identified in 2019 by scientists from the University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, in collaboration with Chinese researchers. The enzyme is capable of cleaving A antigens from tissues, effectively transforming a type A organ into type O.

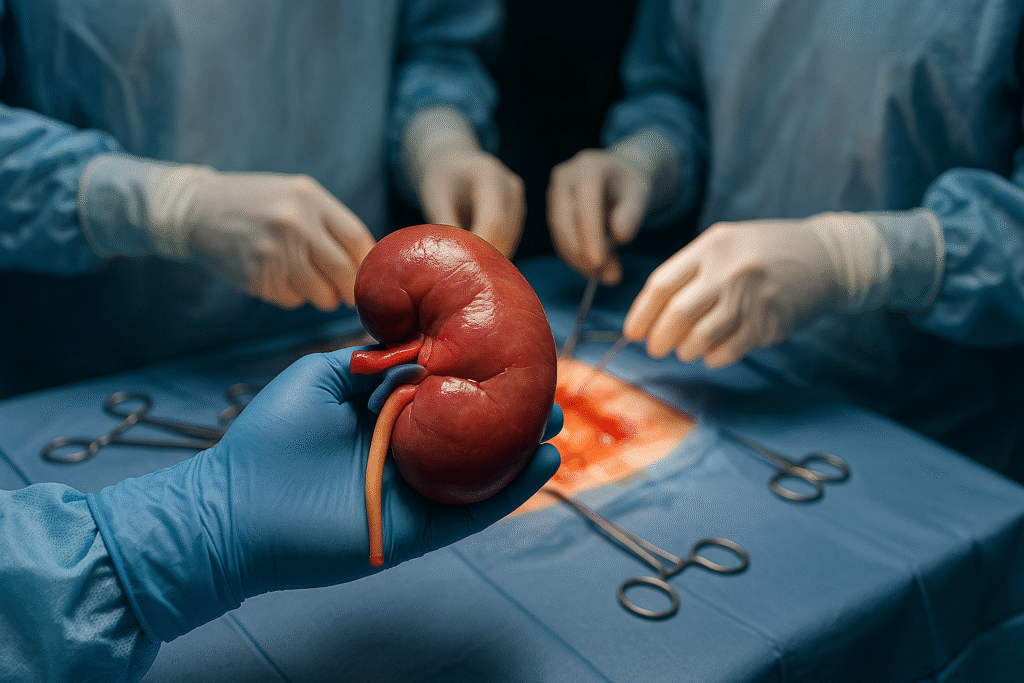

In the latest study, the research team treated a donor kidney from a type A individual with this enzyme, successfully removing the antigens. The modified organ was then transplanted into a 68-year-old man in Chongqing, China, who had been declared brain-dead but maintained on life support, enabling researchers to monitor the transplant without ethical concerns of long-term survival.

The kidney functioned initially, producing urine for six days and showing no immediate rejection signs for two days post-surgery. However, by the end of the first week, immune rejection processes began to occur, ultimately limiting the organ’s survival.

A Step Beyond Laboratory Success

This transplant represents the first attempt to move beyond laboratory models and animal studies to test a universal-blood-type organ in a human body. Earlier, in 2022, the same research group demonstrated that lungs from a type A donor could be converted to type O using the same enzyme. That study, however, remained at a pre-clinical stage without actual transplantation into a person.

According to Stephen Withers, chemist at UBC and senior author of the study, the current results prove the feasibility of organ conversion for clinical use. “This is a critical step forward. While the organ did eventually undergo rejection, the fact that it functioned and was accepted for several days shows the concept has real clinical potential,” Withers stated.

Implications for the Future

The development has been hailed as groundbreaking by transplant experts. Natasha Rogers, a clinician at Westmead Hospital in Sydney, emphasized the potential of the approach: “If the blood type barrier is removed, we could focus on matching other, more complex antigens that govern long-term transplant survival.” This could not only shorten waiting lists but also improve equity in organ allocation, particularly for patients with rarer blood types who face longer wait times.

While the initial results are encouraging, challenges remain. The treated kidney ultimately experienced rejection, suggesting that further optimization of the antigen-removal process is needed. Additionally, clinical protocols must be developed to ensure that enzymatic conversion does not alter other critical aspects of tissue function.

What Comes Next?

The research team plans to refine the enzyme treatment, ensuring more complete and durable antigen removal. Future trials will likely involve additional human test cases, possibly in patients awaiting transplants under controlled clinical conditions, rather than brain-dead recipients.

Beyond kidneys, the same technology could be applied to other organs such as hearts, livers, and lungs, potentially revolutionizing the entire field of transplant medicine. Researchers also envision integrating the approach with immunosuppressive therapies, which could extend organ survival further.

As Withers notes, “This is not the final answer, but it is the opening of a door that has remained closed for decades. The prospect of universal donor organs is now firmly on the horizon.”

If successful, universal-type organs could fundamentally reshape transplant medicine, increasing availability, reducing mismatches, and ultimately saving countless lives.